- Home

- Matthew Condon

Jacks and Jokers

Jacks and Jokers Read online

Matthew Condon is an award-winning author of several novels, works of non-fiction, and is the two-time winner of the Steele Rudd Award for short fiction. His novels include The Motorcycle Café, The Pillow Fight and The Trout Opera. His non-fiction titles include Brisbane and, as editor, Fear, Faith and Hope: Remembering the Long Wet Summer of 2010–2011. His bestselling first volume of the Lewis Trilogy – Three Crooked Kings – won the John Oxley Library Award 2013, and was shortlisted for the Queensland Literary Awards Queensland Book of the Year and the Waverley Library NIB Award for non-fiction. He lives in Brisbane.

PRAISE FOR THREE CROOKED KINGS

‘A fascinating account of the corruption and the power struggles within the Queensland Police.’ Weekend Australian

‘Three Crooked Kings paints a compellingly dark picture.’ Sydney Morning Herald

‘Hailed as the most explosive book of 2013 – a riveting epic and unrelenting tour-de-force which will shock a nation. And it's all true.’ The Chronicle

For the gang – Katie, Finnigan, Bridie Rose and

little Oliver George – with love

SHE DISCOVERED, SHORTLY AFTER, that the man who had just raped her was a policeman.

To add to the humiliation, when he had finished with her, several of his colleagues emerged from closets and doorways where they had been hiding, watching while their friend degraded her.

He thought it was funny. So did his mates. He produced his identification badge and she tried to read his name. She wanted to memorise it, because she was about to do the unthinkable. She was going to report the incident to the police. She didn’t want this to happen to other working girls.

Her name was Mary Anne Brifman, the eldest daughter of the former prostitute, brothel madam and police whistleblower Shirley Margaret Brifman, who had been found dead of a suspected drug overdose on 4 March 1972.

It was Mary Anne who had discovered the twisted corpse of her mother on that Saturday in the small room of the family flat in Bonney Avenue, in the Brisbane suburb of Clayfield. It was Mary Anne who only a year before her mother’s untimely death was being groomed against her will to take over her mother’s brothels in Sydney, before Shirley was charged with soliciting her own child for the purposes of prostitution. When the charge failed to disappear, even though Shirley had been paying off corrupt police like Glen Patrick Hallahan, Tony Murphy and Fred Krahe for more than a decade, she went on live national television and snitched on the whole rotten lot of them.

Following Shirley’s live-to-air interview the Brifmans had returned to Brisbane to hide, to disappear, to keep safe. Shirley and her husband Sonny had lived in the sub-tropical city from the late 1950s until 1963, when the National Hotel inquiry into police misconduct at the famous city watering hole got started. Shirley had been a star witness at the inquiry. At the time she had denied being a prostitute. She rejected any intimate association with Murphy and Hallahan. And no, she claimed, there was most definitely not a prostitution ring working out of the National. It was a classy joint. And what would she know of it anyway? She wasn’t a working girl.

Having perjured herself, Shirley then moved the family to Sydney. Almost ten years later, after blowing the whistle, she returned to Brisbane. Nine months after that she was dead.

Now Shirley’s daughter, Mary Anne, was in her twenties with two children of her own. She was working as a call-out prostitute for an independent outfit called Quality Escorts. The job on this particular night was slightly unusual. The client had asked to meet Brifman in an auto repair shop north of the Brisbane CBD. She accepted the job, but was unaware she was walking into a sexual ambush.

They didn’t know her real identity, of course. They didn’t know she was a Brifman. If they did, and word got back to headquarters, alarm would have spread through the building. It might have been several years earlier, but the stench of the Brifman ‘suicide’ still haunted the corridors of the Queensland Police Force. The tall, gangly officer Shirley knew from the Consorting Squad when she worked in the Killarney brothel over in South Brisbane, Terry Lewis, would rise to become Commissioner. And her friend and lover, Tony Murphy, would stand as the most powerful detective in the force.

In an eerie replica of another time, another Brifman was being used and abused by police. Mary Anne lodged an official complaint against the officer who had raped her and later gave a formal, detailed statement. She too, in a small way, was standing up to those who had disrespected her, just as her mother had done.

For a week internal police investigators visited her home to counsel and placate her. It was clear that while they appeared genuinely concerned for her wellbeing, they also didn’t want the press to get wind of the incident. The constable who raped you, they told Mary Anne, was engaged to be married and had since lost his fiancé because of his actions. He would be exiled to a police station in a remote part of the state.

Mary Anne Brifman didn’t proceed with charges. She didn’t want the world to know she was the daughter of the deceased Shirley Brifman. She didn’t want to live with the shame, so she stepped back into the shadows. From that moment on, for as long as she worked as an escort in Brisbane, she never heard from or came to the attention of the police again. They didn’t dare go near her, the daughter of the ghost of Bonney Avenue.

The Year of the Dragon

By mid-1976 Inspector Terence (Terry) Murray Lewis of Charleville, a dusty town in western Queensland, should already have known that he was in for a stellar year. To begin with, it was a leap year, and he finally got to celebrate his birthday – 29 February – on the actual date. Also, he was born under the Chinese astrological sign of the Dragon, and 1976 was coincidentally the Year of the Dragon. Lewis would be turning 48.

He may not have been familiar with the characteristics of the revered Dragon in Chinese astrology: inflated self-assurance, tyrannical with a stern demeanour, impressed by prestige and rank, devoted to work and lucky with money-making schemes – the Dragon was renowned for leaving a trail of wealth.

By winter Lewis had already had a frank and lengthy discussion with Queensland premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen on the airstrip at Cunnamulla following a country cabinet meeting of the ruling National Party, and he would soon be making a flurry of political contacts. He also wasted not a single opportunity – like his friend Anthony (Tony) Murphy up in Longreach – to disparage the administration of Police Commissioner Raymond (Ray) Wells Whitrod.

The day after Bjelke-Petersen flew back to the big smoke of Brisbane, Lewis returned to his desk in downtown Charleville, in the wooden police station beside the stone bank in the main street. It was a timely visit by the premier. Lewis had had enough of being stuck in western Queensland, and had actually applied for a vacancy in the Commonwealth Police. The Dragon could be stubborn and impetuous at times, and did not like taking orders – they could express flexibility and be amenable to life around them; but only to a point.

‘It crossed my mind to leave – that’s when I applied for a job in the Commonwealth [Police],’ Lewis recalls. ‘I made an application … I think there were two vacancies, one for an Assistant Commissioner somewhere, and a Superintendent. They flew me to Sydney.’

Lewis was picked up at the airport by New South Wales police officer Dick Lendrum who had married Yvonne Weier – one of Lewis’s favourites from his days in the Juvenile Aid Bureau (JAB) in Brisbane in the 1960s.

After his interview (he would later find out that he didn’t get the job), Lendrum arranged for Lewis to meet the New South Wales Police Commissioner Fred ‘Slippery’ Hanson, a foundation member of the legendary ‘21 Division’ unit, formed to smash post-war hoodlum gangs. Hanson had become Commissioner in 1972, succeeding t

he corrupt Norm Allan.

Hanson had made his views on policing very clear not long after he took the top job. ‘Every cop should have a good thumping early in his career to make him tolerant,’ he told the press. ‘A good thumping teaches a young policeman how to get along with people. It’s no use getting police recruits from university, the ones who have never knocked around the lower levels.’

It was rumoured Hanson had been corrupt New South Wales Premier Robert Askin’s organiser of paybacks from illegal casinos, as had Allan.

‘[Dick] took me and introduced me to Fred Hanson, whom I’d never met,’ Lewis says. ‘He’s the one who said [of Whitrod], “Oh yeah, how’s that fat little bastard up there who should be charged with assuming the designation of a police officer?’’’

Meanwhile, retired detective and former Rat Packer Glendon (Glen) Patrick Hallahan was trying to make a fist of the farming life. He had left Brisbane under a cloud following his abrupt resignation from the force in 1972, although for a while continued to live at Kangaroo Point before shifting to acreage in the Sunshine Coast hinterland.

He and the land would be an awkward fit. The big, powerful Hallahan, plagued with bouts of ill-health since the late 1950s, was a city creature, a habitué of bars, wine saloons and restaurants – he relished the bright lights of Sydney. Well into his thirties, he continued to enjoy the nightlife.

In the aftermath of his departure from the force, his good friend – newspaper reporter from the 1950s and now editor of the Sunday Sun newspaper Ron Richards – offered Hallahan an alternative career.

Hallahan, one-time crack detective, receiver of graft from prostitutes, accomplice to criminals in both Brisbane and Sydney and associate to drug dealer John Edward Milligan, would try his hand as a specialist writer and break exclusive stories about crime and corruption. Richards believed that Hallahan could utilise his extensive police (and criminal) contacts, both state and federal, and drum up some rollicking Sunday crime reads.

Despite the fact that the office of the Sun was located in very familiar territory to Hallahan – the heart of Fortitude Valley – life as a reporter didn’t work out. ‘He produced a story using Federal Police intelligence about the arrival of the phenomenon of the car bomb in Australia,’ recalls Des Houghton, then a young journalist on the Sunday Sun, based in Brunswick Street. ‘It caused a bit of a drama and there were questions asked about where he got his intelligence from.

‘Hallahan was aloof. He was a hit with the women in the office. Most of the time he asked for help in how to fill out his expenses.’

After the car bomb scoop, Hallahan virtually disappeared, resuming residence with his wife, Heather, in Obi Obi on the north coast, growing fruit and vegetables and toying with the idea of selling farm machinery. Despite the distance between them he was not lost to his old mate Tony Murphy. The two men remained in regular contact.

During this time in the state’s capital, the classified advertisements in the Courier-Mail newspaper were featuring – in the Beauty and Health section – a relatively new phenomenon to the Brisbane scene – the massage parlour.

In the preceding few years parlours such as the Brisbane Health Studio, The Oriental Bathhouse, The Coronet and others, actually dispensed what they advertised – qualified massages. Each was equipped with bona fide massage tables.

The first Brisbane ‘health studio’ to be prosecuted as a premises used for prostitution was the Carla-Deidre Health Studio in Enogerra in June 1970. A man called Bernard John Pack was prosecuted. The case against Pack established that ‘relief massages’ given to men fell under the prostitution umbrella.

Quaintly, staff of the Temple of Isis were charged in 1971 with breaching the Physiotherapists Act by misleadingly calling themselves qualified masseurs or masseuses.

Police from the Licensing Branch, Drug Squad, Consorting Squad, the Valley Crime Intelligence Unit and even Commonwealth Police regularly visited the parlours, trying to catch prostitutes in the act of sexual congress. On some occasions officers confiscated parlour towels.

If prostitution was detected, the girls were immediately breached. There were no tip-offs about raids, no protection money payments, no charging on rotation. But by 1976, the entire parlour scene had changed.

As Lewis toiled in Charleville, and Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen jetted out on an overseas trade mission, hoping to convince both the British and the Japanese to invest in Queensland’s limitless reserves of coal, and state Cabinet debated sand mining on Moreton Island, gentlemen were being invited to explore the pleasures of female ‘masseuses’ across Brisbane city.

There was the Penthouse Health Studio at 141 Brunswick Street, Fortitude Valley. There was the Kontiki at 91 Gympie Road, Kedron. ‘Have you met our pretty and talented girls at Kontiki? Well they’re just longing to entertain you the way you enjoy the best.’

There was the Fantasia Health Spa at 187 Barry Parade, Fortitude Valley. And the Golden Hands Health Salon at 1145 Ipswich Road, Moorooka. ‘Come and meet our lovely talented girls …’

In the Year of the Dragon, a lot of money was changing hands in Brisbane after dark, and men like corrupt former Licensing Branch officer Jack Reginald Herbert picked up the scent.

The luck of the Dragon would touch Lewis not once, but twice, in just a matter of months. Coming events – an act of police brutality in far-off Brisbane, and a bungled drug raid in even remoter Far North Queensland – would trigger Commissioner Ray Whitrod’s demise. They would also, as if by magic, open a clear path for Lewis to the summit of the Queensland Police Service.

A Lemonade in Blackall

Just as Police Commissioner Ray Whitrod and Police Minister Max Hodges had paid a visit to Inspector Terry Lewis in Charleville in the winter of 1976, taking morning tea in the station and keeping tabs on the banished Rat Packer, they continued their tour 300 kilometres north to remote Blackall.

A grazing town perched on the Barcoo River and home to the historic Blackall Woolscour, the township evolved mainly as a service centre to surrounding properties. On one of those – Alice Station – in 1892, shearer Jack (Jackie) Howe broke colony records when he shore with hand shears 321 sheep in seven hours and 40 minutes and catapulted himself into folklore.

As was the custom, Whitrod and Hodges’ visit necessitated a function in one of the local hotels, which was attended by 30 to 40 dignitaries, graziers and of course the local police. The Blackall police station was operated by sergeant in charge Les Lewis and four other officers. At the event, Les Lewis was sipping a glass of lemonade when he was approached by Minister Hodges.

‘What are you drinking, sergeant?’ Hodges asked him.

‘Lemonade,’ Sergeant Lewis replied.

‘What would you usually drink?’

‘Beer,’ he replied. ‘But I never drink [alcohol] in uniform.’

Hodges pointed out that even the Commissioner of Police was drinking a glass of wine in full uniform, and said to the barman: ‘Give the sergeant a beer.’

As the two men engaged in conversation, the Minister immediately expressed his dislike of the inspector in charge of the Longreach district (which took in Blackall, 213 kilometres away), Tony Murphy.

‘Murphy’s got a chip on his shoulder,’ Hodges remarked. ‘So has [Terry] Lewis.’ Hodges went on to tell him that Whitrod planned to transfer Terry Lewis from Charleville to Innisfail in Far North Queensland, ‘to keep him as far away as possible from Brisbane and the Commissioner’, and that Murphy would be staying put in Longreach ‘until he learned to smile’.

Sergeant Les Lewis, who worked well with Murphy and believed the famous detective from Brisbane had done a good job in Longreach, told Hodges that Murphy was expecting a transfer to Toowoomba where his wife and children had settled.

Hodges said it wasn’t going to happen. ‘Hodges was very firm,’ recalls Lewis. ‘He was the boss.’

A few days late

r, Murphy’s car pulled into the police yard in Blackall. He was on his way down to Toowoomba to see his wife, Maureen, and the kids. The drive – over 1200 kilometres – also took him en route through Charleville.

Sergeant Les Lewis felt compelled to relay to his boss details of the meeting with Hodges and Whitrod. ‘I’ve got something to tell you if you promise not to take it further,’ he said. He told of Hodges’ refusal to move Murphy out of Longreach until he ‘learned how to smile’.

Murphy immediately got out of the car in a rage and repeatedly kicked the tyres of the vehicle. ‘Those bloody bastards,’ he shouted.

Murphy then ‘took off out of the yard’ and headed for Terry Lewis in Charleville. In Murphy’s mind, Hodges’ remarks about himself and Terry Lewis constituted the persecution of senior officers in the Queensland Police Force.

He would most certainly be taking the matter forward.

Love in the Lido

Down in the mean streets of Kings Cross, Sydney, once plied so successfully by former Brisbane madam Shirley Margaret Brifman, another young prostitute, Anne Marie Tilley, was working the lanes and backstreets.

Tilley, even before she hit her teenage years, was steeped in the business of prostitution. Her foster father had once been a driver for the legendary Sydney madam Matilda (Tilly) Devine of the Razor Gang era in the 1920s and 1930s. He told her many stories through her girlhood. At the age of 11, Tilley was entranced by the popular 1963 Billy Wilder film, Irma La Douce, a musical comedy about a policeman who falls for a prostitute in Paris. In the movie, honest gendarme Nestor Patou (Jack Lemmon) unwittingly begins arresting call girls who are favoured by corrupt senior police and is thrown out of the force. By fate he becomes close friends with prostitute Irma (Shirley MacLaine) and eventually declares his love. Tilley adored the luxuriant lifestyle of the on-screen prostitutes. She adored Irma’s fluffy white dog. She knew this was the life for her.

The Night Dragon

The Night Dragon Jacks and Jokers

Jacks and Jokers Little Fish Are Sweet

Little Fish Are Sweet Three Crooked Kings

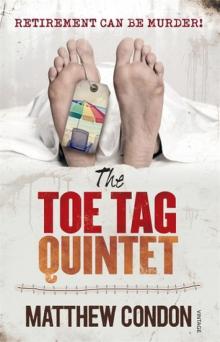

Three Crooked Kings The Toe Tag Quintet

The Toe Tag Quintet