- Home

- Matthew Condon

The Night Dragon

The Night Dragon Read online

Matthew Condon is a prize-winning Australian novelist and journalist. He began his journalism career with the Gold Coast Bulletin in 1984 and subsequently worked for leading newspapers and journals including the Sydney Morning Herald, the Sun-Herald, Melbourne’s Sunday Age and the Courier-Mail. He has written ten books of fiction, including The Trout Opera, and is the author of the best-selling true-crime series about Queensland crime and corruption – Three Crooked Kings (2013), Jacks and Jokers (2014), All Fall Down (2015) and Little Fish are Sweet (2016).

For my wife, Katie Kate

‘ … he is colour blind in the red, green and brown colours … he is hard to frighten … he is very methodical … he does not like sunlight because he is very fair-skinned … he has the tattoo of St George and the Dragon on his chest, on his back and both legs.’ —Witness statement about Vincent O’Dempsey given to the Crime Intelligence Unit, Brisbane 1974

‘He takes you in the middle of the night, like an angel, and you’re gone for good.’ —Witness at Vincent O’Dempsey’s committal hearing, Brisbane 2015

Vincent O’dempsey appeared in the glassed-in dock of a Brisbane court, his hair slicked back, his gaze shifting to all quarters of the courtroom. Even in profile, he had a bird-like countenance. His penetrating black eyes and the slight, almost imperceptible movements of his head were like that of a hawk, attuned to the slightest shift in the landscape, or the potential for a trap.

In criminal circles his presence had been felt since the 1960s, and while he had brushed up against the judicial system for various petty offences, he remained an ominous figure at the edge of the firelight. Here was the person other serious criminals described as the most feared man in the Australian underworld. It was rumoured he was a cold-blooded killer the likes of which this country had never seen – the man with his own private graveyard that, as Warwick locals quipped over the years, was so full that the bodies had to be buried upright to save space. Now, here he was in the full light of day, like some bogeyman in a dark children’s fairytale, or an ancient myth, come to life and captured in the bowl of the court dock. The legendary Vincent O’Dempsey – pugilist, bird breeder, alpaca farmer, bushman and munitions expert out of Warwick, Queensland.

In certain circles he was nicknamed Swami the Magician, because he made people disappear. Others called him the Angel of Death who came for you at night, or Silent Death. When he was imprisoned in his late-twenties for break, enter and steal, and possession of an unlicensed firearm, word filtered through Boggo Road Gaol that O’Dempsey already had at least one murder notched on his belt.

For the next fifty-odd years he would intermittently do time for various drug and weapons offences, and all the while the myth grew around him. In the press and even in State Parliament the speculation persisted that various cases of people missing and presumed murdered were the work of this one man. Yet, O’Dempsey always denied the allegations of murder levelled against him, and despite being suspected of multiple murders on the recommendation of a coroner in 1980, the case never made it to court. For decades, even his own criminal associates wondered: How did he get away with it?

It wasn’t until more than half a century after his supposed first kill that police would unearth a criminal accomplice who was prepared to testify against O’Dempsey in court.

Finally, time had caught up with the Night Dragon.

Day of Reckoning

It was the first day of winter – 1 June 2017 – and by 9.45 a.m. in the Queen Elizabeth II Courts of Law building on George Street in Brisbane’s CBD, the public gallery was almost full. For more than a month a core group of spectators – detectives, civilians, legal observers, the media – had been gathering in the watery morning light outside Court 7 with its view north to the city’s old convict windmill on the Wickham Terrace ridge. They had gotten to know each other during the course of the murder trial of Vincent O’Dempsey, 78. They had come by train and by car and by foot. There were nods and banter.

As the weeks progressed, the appearance of an unknown face in the crowd would prompt observation and questions. ‘Do you know who that is?’ ‘Are they with O’Dempsey’s side?’ These spectators had become bound by the mechanics of the trial, with its many obvious and hidden parts, its occasional levity, and enduring horror.

On 16 January 1974, a woman called Barbara McCulkin and her two daughters, Vicki, 13, and Leanne, 11, had disappeared from their modest rental home at 6 Dorchester Street, Highgate Hill, in South Brisbane. They were never seen again.

The old Queenslander in Dorchester Street has changed little in the past four decades. Perched on a steep, narrow block, its stumps short at the front and tall at the back, the standard timber and tin worker’s cottage was like many that proliferated the city’s working-class inner suburbs a century ago.

But on 16 January, 43 years earlier, life stopped at this address. At the time of her presumed murder, Barbara was married to local petty thief and low-level gangster Robert William ‘Billy’ McCulkin. A heavy drinker and perennial layabout, he had left the family home for another woman in late 1973 but stayed in touch with Barbara and the kids.

The vanishing of the McCulkins came less than a year after a string of arson attacks in Brisbane’s notorious Fortitude Valley precinct. One of those fires, at the Whiskey Au Go Go nightclub on 8 March 1973, had killed 15 innocent people in what was then considered Australia’s biggest mass murder.

Two men – John Andrew Stuart and James Richard Finch – were swiftly arrested and convicted of the crime. But Barbara, who worked in a snack shop in the city and did her best to provide for her children, knew some powerful truths about the fires. Her house in Dorchester Street had become a veritable clubhouse for McCulkin’s criminal associates, including Vincent O’Dempsey and a local gang who would later become known as the Clockwork Orange Gang. In the months before and after the Whiskey Au Go Go tragedy, Barbara had picked up enough information in that small house, with its VJ timber walls, to put away not only many of Billy’s friends but McCulkin himself.

When Barbara and the girls vanished, rumours immediately circulated that O’Dempsey, a vicious career criminal along with his sidekick, Garry Reginald ‘Shorty’ Dubois, had done away with the McCulkins because of what Barbara knew about the Whiskey. Now, more than four decades later, both O’Dempsey and Dubois had been found guilty of multiple charges against the McCulkins, including murder, rape and deprivation of liberty. They were tried separately, but on 1 June 2017, the day of reckoning, they were to be sentenced for their crimes by trial judge, the Honourable Justice Peter Applegarth.

Relatives of O’Dempsey and Dubois, as was their custom during their respective trials, sat in the gallery seats directly behind the extended glassed-in dock to the left of the court behind the bar tables. One of Barbara McCulkin’s brothers, Graham Ogden, with his wife and children, also took their regular seats at the rear of the court.

At precisely 9.55 a.m. Dubois was escorted to the dock by correctional officers via a side door. During both his committal hearing and trial, Dubois showed in his gait and demeanour a total indifference to the gravity of proceedings. Small of frame, head shaved, dressed in khaki trousers and a floral shirt that appeared too big for him, Dubois walked to the dock like a truculent child, his feet dragging slightly, his lined face a rubbery, blank palette. Dubois sat at the far end of the dock and placed his right arm along the bench seat like he was going for a Sunday drive in one of his beloved Studebakers.

‘So, that’s Shorty,’ someone said from the crowd in the packed courtroom.

Thirty seconds later O’Dempsey entered the court. Of average height with dark, oily hair, he sat at the other end of the dock to Dubois and fiddled with t

he courtroom hearing apparatus. For the duration of his trial, and on this day, he was dressed in a dark suit with a white shirt and tie, and slip-on black loafers. He wore his suit like a farmer going to a funeral.

In the quiet before the opening of proceedings, and with O’Dempsey’s ears sufficiently connected to the court sound system, the word ‘psychopath’ was muttered from somewhere deep in the gallery. Three correctional officers took their seats at both ends of the dock. Justice Applegarth entered the courtroom at 10.10 a.m., having been delayed by another case.

‘It’s reasonably late,’ Applegarth said. ‘Let’s get on with it.’

Tony Glynn, QC, O’Dempsey’s legal counsel, in his horsehair and black robe, stood. ‘My client now wishes to say something,’ Glynn said.

‘If someone wants to express remorse, I’ll hear it,’ Applegarth replied. Applegarth had proven himself to be supremely patient and of even temperament during the two lengthy trials that had contained their fair share of frustrating legal argument, given the high-profile nature of this, one of Queensland’s oldest cold cases. He had dealt with interruptions from the gallery, witnesses who didn’t want to be on the stand, elderly witnesses who were hard of hearing and carried other infirmities, along with the usual potholes a complex trial generates. And now, moments before his sentencing remarks, the convicted murderer, who had continued a reign of terror for most of his life, decided he wanted to address the court. ‘What does he want to say?’ Applegarth asked.

Glynn said a handwritten note had been provided to O’Dempsey’s solicitor, Terry O’Gorman, earlier that morning.

His Worship, not convinced he should give O’Dempsey an audience if he didn’t know what he was about to say, was provided with the note. He asked Crown Prosecutor David Meredith his opinion on this highly unusual development, then concluded that O’Dempsey’s note was completely unconvincing as a ‘protest of innocence’.

He went on to say: ‘… my view is that anyone who hears this will treat it with the merit it deserves, coming from someone who has been convicted of three murders … I’ll allow him to make this little speech.’

Applegarth leaned back in his chair. It was 10.21 a.m.

O’Dempsey stood. ‘I’m here before you today wrongly committed, on false testimony,’ he said in a weak voice, referring to the evidence of three chief witnesses. ‘[The] false evidence given by these three … was secured by [Detectives] Virginia Gray and Mick Dowie … [I] never had the slightest reason to harm the three McCulkins in any way, nor [did] my co-accused.’

The public gallery was tense. In some quarters, incredulous.

O’Dempsey argued that the issue of the nightclub fires in early 1973, in particular the arson attack on the Torino nightclub and restaurant, followed less than two weeks later by the Whiskey Au Go Go atrocity, had ignited in his trial a ‘prejudicial smokescreen’. He was adamant he had no knowledge of both fires, despite the fact that a former criminal associate had told Dubois’s trial that both O’Dempsey and Barbara’s husband, Billy McCulkin, had organised the Torino’s fire and that members of the Clockwork Orange Gang had carried it out for the princely sum of $500.

O’Dempsey concluded his speech with a sputter, tangling his words, something at odds with the constant assertion of those who knew him that he had an IQ off the scale. (During his questioning in the 1980 coronial inquest into the murders of Barbara McCulkin and her daughters, O’Dempsey famously answered all 47 questions put to him with ‘No comment’, including when he was asked his name.)

O’Dempsey resumed his seat but before Justice Applegarth proceeded with the sentencing he took O’Dempsey to task on his unexpected speech to the court, especially in relation to his declaration of non-involvement in the Whiskey Au Go Go mass murder.

After outlining O’Dempsey’s lengthy criminal history, and then hearing an emotional and moving victim impact statement from Graham Ogden, brother of Barbara McCulkin (read by his son, Brian), Justice Applegarth described O’Dempsey’s assertion of a prejudicial smokescreen as ‘interesting’. He said a portion of prejudicial evidence he had earlier excluded from O’Dempsey’s trial was a conversation that was overheard between the father of chief witness Warren McDonald and O’Dempsey on a boat trip sometime in the 1990s.

In light of O’Dempsey’s challenge, Justice Applegarth told the court the nature of that conversation. According to the evidence, O’Dempsey was told by McDonald’s father that convicted Whiskey Au Go Go ‘fire bomber’ James Finch was coming back to Australia to implicate O’Dempsey in the Whiskey atrocity.

O’Dempsey allegedly replied: ‘If he comes back I’m screwed, so he’ll have to be knocked [killed].’

Justice Applegarth said that despite O’Dempsey denying any involvement in the Whiskey, ‘there’s evidence in that form’ that he was involved in the crime. The judge said he was revealing this because ‘things should be said in the interest of completeness’. He later said that when O’Dempsey asserted he had nothing to do with the fire, the public needed to know there was evidence ‘that he was involved’.

With that on the record, Applegarth began his formal sentencing remarks. ‘Vincent O’Dempsey, you are to be sentenced on one count of deprivation of liberty and three counts of murder,’ Applegarth commenced.

‘Garry Reginald Dubois, you are to be sentenced on one count of deprivation of liberty, one count of manslaughter, two counts of rape and two counts of murder. The offences were committed late on the night of 16 January 1974. Your victims were Mrs Barbara McCulkin, aged 34, and her daughters, Vicki, aged 13, and Leanne, aged 11 …’

In every city in the world there are cold case crimes that, if they’re allowed to remain unresolved for long enough, haunt the landscape. It’s as if these silent victims are saying – we are not at rest, don’t forget us.

Brisbane has had its fair share of these cold ghosts. Cases that became burrs in the fabric of the community. There is a sense that we have somehow failed the victims and their families, by not tying things off. These tragedies scar our history and refuse to heal.

The disappearance of snack shop attendant Barbara McCulkin and her two young daughters was another suppuration in Queensland’s criminal history. A lot has been written about the McCulkin case over the years. And with years come rumours on top of rumours. Barbara and her daughters were most certainly dead.

So where were the bodies?

Buried in a lift shaft of a high-rise office block in the centre of the Brisbane CBD, some said. In a dam wall outside the city, said others. The steady mistral of whispers and conjecture had continued right up to the guilty verdicts in 2017 against O’Dempsey and Dubois.

But this was a crime that had very deep roots and was many generations in the making. It was a story of violent family history and of migration, of working the soil, of cruelty and pain. It included troubled youths in reform schools emerging as hardened criminals who would come together to wreak havoc on their community; rape and slashed throats and victims pleading for their lives; gangsters and hitmen. It included police and political corruption and a conspiracy that remained hidden for more than four decades, which allowed a maniac who could have walked straight out of a medieval tale about dragons and a knight laying waste to thousands of innocent lives, to kill at will. All in the shadow of God.

Clans

The history of the O’Dempsey family may have stretched back to the bloody Anglo-Norman invasions of Ireland in the late 12th Century, when Dermot O’Dempsey, Chief of Clanmalier, defeated Richard ‘Strongbow’ de Clare in the 1170s, but as the centuries passed and the clan dissipated in both power and wealth, there was little to suggest that the family, steeped in Catholicism, might produce a modern killer.

In fact, the Queensland branch of the O’Dempseys presented as nothing more than respectable farming types, despite a persistent reputation for rabblerousing and troublemaking when it came to standing up for their right

s. By the 20th century, this was an ever-sprawling family dedicated to community service and the church. Several O’Dempseys would, through the decades, take holy orders. And while many O’Dempsey men would prove fierce on the sporting field and in the boxing ring, they would still turn up for Sunday Mass, black eye or not, and observe the diet on the Sabbath with communion bread and holy water.

It wasn’t until the arrival of Vincent O’Dempsey on 2 October 1938, that a flaw in the O’Dempsey clan fabric would be exposed. Vincent was an anomaly, so at odds with his parents, his upbringing, his respectable environment, that he could have been spawned from a different family altogether.

Historic photographs would reveal, however, an eerie resemblance between Vince and his great-grandfather, James Patrick. In pictures the two O’Dempsey men share an identical jawline, and deranged eyes, so unsettling they dominate the face.

On 8 August 1855 James Patrick Dempsey, 26, and his new bride, Johanna, 18, boarded the Sabrina at Liverpool dock in north-west England to start a bright new future in Australia. As Robyn Manfield wrote in her book, Chronicles of the O’Dempsey Family from Rathcannon, County Tipperary to Upper Freestone, Queensland 1855 – 1997:

Under the Irish clan system, O’Dempsey was an honoured and respected surname. However, during the sixteenth century, under English Law, the O’Dempseys were proclaimed outlaws, stripped of their property, and exiled from their native territory of Clanmaliere. By 1793, the family was living in Rathcannon … and were called Dempsey.

James Patrick had spent most of his life working on his father’s farm in Rathcannon, County Tipperary, but after leaving school had entered the Catholic Seminary and studied to become a priest. When James and his young wife sailed on the Sabrina, Johanna was already pregnant with their first child, Patrick. The Dempseys (the ‘O’ prefix to the family name was returned by James Patrick upon settling in Australia) were two of 276 passengers aboard the Sabrina, and news reports would later confirm that the journey to Australia had been a difficult one. The ship arrived in Moreton Bay on Wednesday 28 November. Apart from passengers and crew, the ship was also carrying clocks, iron and vinegar.

The Night Dragon

The Night Dragon Jacks and Jokers

Jacks and Jokers Little Fish Are Sweet

Little Fish Are Sweet Three Crooked Kings

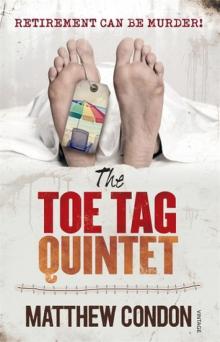

Three Crooked Kings The Toe Tag Quintet

The Toe Tag Quintet