- Home

- Matthew Condon

Three Crooked Kings Page 2

Three Crooked Kings Read online

Page 2

Later that morning, the new recruits entered the lecture room of the police depot and were asked to take the oath by Chief Inspector John Smith. (Even the cadets had heard the rumour that Smith had changed his name by deed poll from ‘Schmidt’ after the war.) The men were told that each and every one of them had an opportunity to rise to the top of the Queensland police force. There was no casual banter or congratulation. With that, the chief inspector left.

‘Get down to Roma Street,’ they were ordered.

The new constables proceeded outside to Petrie Terrace. Across the pubs and shopfronts, residents of Rosalie and Bardon and Paddington were cleaning up after the storm, gathering broken branches, inspecting damaged roofs and attempting, in vain, to right fallen flowers.

Lewis – daunted, conspicuous in his new uniform (the trousers were a little baggy, the jacket too tight) in the punishing humidity – and his colleagues hopped a city-bound tram – no fare, police officers travelled for free – and went directly to Roma Street police station, in view of Lewis’s old counter at the Liquid Fuel Control Board, and reported for duty.

Within moments, Constable T.M. Lewis (No. 3773 on his uniform; No. 4677 when mentioned in any correspondence) was walking down Albert Street and into the crosshatched streets and noon shadows of Brisbane city’s heart. He was officially on duty.

At some point in the next few months, he secured an old and unused 362-page leather-bound government minutes book and began a diary of personal arrests.

On page one he wrote a brief summary of his antecedents, schooling, and employment history. On page two he glued in his typed farewell card from the Liquid Fuel Control Board. On page three he affixed his final examination paper from the police depot.

And on page four he recorded the details of an early arrest, William Joseph Thornhill, twenty-one years of age: ‘That on the 11th day of June 1949, at Brisbane, in a Public Place, namely the Hong Kong Café in Queen Street, he did behave in a disorderly manner.’

Terence Murray Lewis was on his way.

Constable Lewis on the Beat

In his first few weeks as a constable, Lewis was based out of the old two-storey Roma Street police station. The basement housed the Brisbane Police District, the next floor the Traffic Branch, and the top floor the Licensing Branch (including a ‘wet bar’ – beer only).

Roma Street was dubbed ‘The Order of St Francis’, for its heavy representation of Roman Catholics. Similarly, the Woolloongabba CIB was called ‘The Vatican’.

Lewis was quickly seconded to traffic and performed point duty on several of the city’s major intersections. He oscillated between the 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. and 3 p.m. to 11 p.m. shifts.

With the majority of business concentrated in the city grid, commanded down its centre by Queen Street, Lewis was keeping order in a hive of trams, cars, lorries in and out of the Roma Street markets, and pedestrians. Brisbane’s population was around 442,000.

On point duty, Lewis worked alone. And despite the mundaneness of the task, he managed to collar a few drunks and vagrants whose faces would become familiar to him over the years. There was Bill Millwood, forty, who behaved in an indecent manner in Albert Street. And Ed Ebzery, forty-four, who in Queen Street called Lewis a ‘fucking choco cunt’.

All the while, he was getting to know and understand the rhythm of the city and its people. He became acquainted with members of the legal fraternity and journalists, with shopkeepers and business operators. He began to understand who drank where, the patterns of vagrancy and begging alms, the different complexions of the city during the day and at night.

Not far away, up at the police depot, a former London police officer – Jack Reginald Herbert, twenty-four – was jumping through the same training hoops as Lewis had only months before, eating in the same canteen and bunking down in the evening in the latticed dormitory on Petrie Terrace.

Herbert had drifted to Australia after the war, keen for sunshine and adventure, and had kicked around Victoria and hitchhiked to Toowoomba with a mate before deciding to join the police in Brisbane.

He was a restless man, always on the lookout for a better deal. ‘Until now I had been a young bloke in a hurry to be somewhere else,’ he reflected in his memoir. ‘But I knew that sooner or later I would need a place to settle down. I never imagined that place would be Brisbane but at the same time I knew I hadn’t been happy anywhere else.’

In December 1949, he spotted a young redhead across the dance floor at the famed Cloudland Ballroom in Bowen Hills. Her name was Peggy, and she was a typist at the Immigration Department offices in the city. It was Peggy who gave the restless Herbert a reason to stay in Brisbane.

By mid-1950 Lewis found himself behind the handlebars of a police motorcycle. Here, he encountered some action.

His first mention in the press as a policeman came after a wild, sixty-miles-per-hour chase on 25 August. At about 7.40 p.m., Lewis and another motorcycle cop noticed three youths travelling in a utility truck along Main Street, Kangaroo Point. The vehicle did not have its headlights on.

They stopped the driver – Norman Gleeson, twenty, a seaman – who said the truck lights had fused and he had left his driver’s licence at home. Also in the truck were John Croke, seventeen, and Alexander Philp, twenty, both labourers. Lewis said they’d follow Gleeson home to check his licence.

The truck drove off at twenty-five miles per hour but soon hit forty and the chase was on. Gleeson sped through stop signs, crossed to the opposite side of the road on numerous occasions, swept in front of trams and narrowly missed a group of pedestrians in Fortitude Valley.

Lewis repeatedly drew alongside the vehicle and shouted to the driver to stop, but Gleeson attempted to run him off the road. Croke then hurled three milk bottles at their pursuers and one shattered on impact. The youths were ultimately apprehended after several hair-raising miles through the suburbs of Spring Hill, Morningside and Woolloongabba.

The chase was news: three youths fined after wild joy ride. After nineteen months in the job, Constable T.M. Lewis had made the newspapers.

He also received, as a result of that job, his first official favourable citation from the chief inspector: dated 25 September 1950, Lewis and Duncanson ‘of the Traffic Branch, Brisbane, are commended for the good work performed by them in these cases. Have this memorandum noted by the Police concerned, and returned.’ It was signed ‘J. Smith’.

Over the next two months Lewis continued to pursue more drunk drivers across the city before noticing gazetted vacancies in the CIB.

The recruitment drive was part of a major restructure of the CIB, courtesy of a six-month European study tour of police methods – particularly those of Scotland Yard – taken the previous year by Brisbane CIB chief Tom Harrold and Sub-inspector Frank Bischof. The new crime-busting techniques were to be implemented by early 1951.

Down at CIB headquarters they were putting the finishing touches to a new ‘information room’, where detectives and radio operators would control the movements of squad cars across Brisbane. As part of the fresh plans, the public would be able to phone the CIB – at no cost – and report suspected crimes or suspicious individuals. The plan was based on Scotland Yard’s revolutionary 999 system.

In addition, the Survey Branch of the Lands Department was preparing the most comprehensive map of Brisbane and its suburbs – from highway to back alley – ever attempted. It would be installed in the information room and affixed with variously coloured small flags apportioned to different types of offences.

As the Courier-Mail reported, ‘The information officer will then be able to tell at a glance where more concentrated police effort is required and will switch cars from quiet areas to the one needing attention.’

It was the type of exacting detail that would have excited Lewis. He had, to that point, been a diligent officer. He kept his police diaries up to date, co

ntinued recording arrests in his own personal logbook, which had reached fourteen pages, and he’d been commended by the upper hierarchy.

He was only twenty-two in November 1950, when he went to work with the big boys in the old church buildings at the corner of Elizabeth and George streets. He would leave the stiff-collared uniform behind and replace it with a jacket and tie.

And Lewis would no longer work alone, but be partnered on jobs – theft, robbery, assault, prostitution, even murder – with fellow CIB officers. One of the first of those partners would be Tony Murphy.

Hallahan Comes Home

As Lewis was chasing hoodlums across Brisbane on his police motorcycle, Glendon Patrick Hallahan’s dream of a future in the RAAF evaporated when his father fell gravely ill back in Toowoomba. Hallahan returned home from the air force base in Wagga Wagga to help out with the family ice and milk run, but the business soon foundered.

The tall, dapper Hallahan was just eighteen years old and even then was showing a restless nature, constantly on the alert for greener grass. He would chase it for the rest of his life.

After the family business was sold, he took work as a labourer with the Forestry Department and was based in Cooran, a small, pretty village nestled in a valley between Noosa and Gympie.

Cooran had the ubiquitous railway hotel, a school of arts, a king street. In the 1920s its bananas were proudly displayed at the Brisbane exhibition every August.

The town also had a plethora of saw mills, a toy factory, a joinery, and a thriving dairy industry. By the time Hallahan arrived, the town sported its very own branch of the Queensland Band of Hope Young People’s Temperance Union.

Hallahan, as with Lewis and Murphy, hopped from job to job looking for a purpose. Unlike the early work of those men, however, he immersed himself in physical labour. He would soon leave Cooran and try his hand at cutting sugarcane up the Queensland coast.

It was unusual, given his intelligence, and his aborted bid for a RAAF apprenticeship. There was plenty of employment for canecutters after the Second World War, but it was serious, back-breaking labour, working in gangs for more than forty hours a week with a seventy-centimetre wood-handled cane knife.

Around 1950, farmers began burning their sugarcane crops prior to harvest to expunge them of vermin and rubbish, but the stalks were sticky with sugar syrup and the cutters would finish the day covered in soot.

At some moment, bearing down on a clutch of five-metre cane stalks with his machete, brushing away bees attracted to the sugar, a career in the police force entered Hallahan’s mind.

Sub-inspector Bischof Investigates a Gross Fraud

Labor Premier Edward (Ned) Hanlon secured another term after the 1950 state election thanks to his pre-installed gerrymander, an act that would similarly advantage the Country Party if and when it ever took power after seemingly endless years of Labor domination.

But the purse-lipped, autocratic Hanlon, his health in the early stages of decline, came under ferocious attack from members of the Opposition, in particular the eloquent businessman and leader of the Liberal Party, Thomas Hiley, over an apparent irregularity in election ballot papers at a polling booth in the riverside suburb of Bulimba, just east of town.

As the political furore was building in the final weeks of 1950, Lewis was ensconced in the CIB and assisting in his first big arrest as the new boy in the branch.

The defendant, apart from committing dozens of break and enters, had stolen 174 pounds from the trustees of the Hibernian Australasian Catholic Benefit Society, Southern Queensland District. He was prosecuted and jailed.

Among the officers on the case were Detective Senior Constable A.B. (Abe) Duncan, Detective Sergeant W. Beer, Police Constable T.M. (Terry) Lewis, and Police Constable A. (Tony) Murphy. All officers received for their work a letter of appreciation from Inspector Jim Donovan, a Catholic.

Before Christmas, Lewis would nab some car thieves, nick two men who had stolen eight tons of firewood, and arrest a Moorooka housemaid for stabbing a man with a butcher’s knife after a party fuelled by cheap wine.

Lewis loved the CIB work, relished being around tough senior police like Bischof, Norm Bauer, Don (Buck) Buchanan, and Syd Currey. He worked obsessively, putting in long hours. He was by no means physically imposing with his thin frame and his narrow, sloped shoulders, but he discovered a talent for observation – vehicle plates, items of clothing, faces – and was in thrall of the architecture of hierarchy. Throughout his career he would always refer to senior officers by their rank, friends or otherwise.

From the outset he was perceived by many in the branch as akin to the kid who always came top of the class but desired to hang around the tough guys. By association, that gruff and powerful exterior might rub off on him. Some instantly assessed Lewis as ‘weak as piss’. He was the runner, the messenger boy, the fresh recruit who dashed out at lunchtime for pies for the senior men.

The rumour in the branch at the time was that the only reason the powerful, punting-addicted Bischof had any interest at all in the young constable was that Lewis was connected, via his mother, to the Hanlon family – rich, as it was, with horse trainers, jockeys, and aficionados of the track.

In January 1951, Bischof – always available for investigations with a political connection – was put in charge of the Bulimba poll fraud case. Following the 1950 state election, the Liberal Party candidate for Bulimba had asked for a recount and the issue was investigated by the acting chief justice, who concluded in a 10,000-word report that corrupt practices in relation to the vote had taken place. Eleven fake ballot papers were discovered.

Over the next two months the government and police were criticised for the tardiness of Bischof’s investigation, then, on the morning of 9 March, Queensland’s chief electoral officer, long-time public servant Bernard McGuire, was arrested at his home in Kedron Park and charged with having forged a ballot paper.

McGuire would face three trials over the fraud, with each jury disagreeing and a nolle prosequi entered. He took some long service leave in the aftermath of the drama.

What the Bulimba case ignited, however, was an enduring enmity between Liberal leader Hiley and the police force, in particular Frank Bischof.

In parliament in March, Hiley baited Bischof, hinting that the inspector had ignored evidence of a ballot paper fraud in another electorate. Then, on the evening of 4 April 1951, at a function in support of a Liberal by-election candidate, Hiley unleashed an extraordinary attack on the police and the government.

In a forty-five-minute tirade, he declared that Labor had protected major SP bookmakers from police action. He added that the government was misusing the police force and telling them how to conduct political investigations. He further alleged that one of the state’s biggest SP bookies was a member of the Police Boys’ Welfare Club and a personal friend of Premier Hanlon.

‘Every politician knows that the handling of SP in this state has become a highly political racket,’ Hiley reportedly said.

He continued his attack the following week, naming an Ipswich SP bookie – the brother of a state Labor member of parliament – who had been ‘protected’. The police force, Hiley said, wanted to do its job but had to ‘close its eyes’ when an issue involved politics. He said some SP bookies were ‘the Royal favourites’ and enjoyed protection.

‘One of the operators in Ipswich is a J. Marsden,’ Hiley said. ‘When I noticed that Marsden was untouched though every other operator in Ipswich was put through the hoops, I wrote to the Police Commissioner. Shortly afterwards Marsden for the first time was convicted.’

Hiley was hinting at the existence of a so-called Premier’s Fund – a slush fund used to finance favoured candidates in state elections. The word was that the money – cash only – was provided by SP bookies, collected by the private secretaries of ministers of the day, and delivered in black bags to the p

remier’s office.

After his twin-forked verbal spray, Hiley was naturally criticised by the government, but a slow fuse that would burn across decades had been lit, and Hiley and Bischof would memorably collide again in the future.

The Clever Mr Whitrod

Back from the war, where, during his two tours of duty as a RAAF navigator, he specialised in coastal surveillance, Raymond Wells Whitrod returned to the Adelaide CIB. He was war weary.

Whitrod’s two small sons barely recognised their father, and he had difficulty adjusting back to civilian life. In the CIB, he recognised some old faces and saw many more new ones.

Then, out of the blue, he received a phone call from a well-known Adelaide lawyer named Bernard Tuck. Whitrod recalled the conversation in an interview:

[Tuck] said, ‘I don’t suppose you know what I want to talk to you about’. And I said, ‘Yes, I do . . . You’ll be looking for some good field investigators . . . I’m one of the best.’ And he said, ‘How did you know that I’d be looking for field investigators?’ I said, ‘Well, Mr Tuck, you were a very prominent lawyer in Adelaide. You suddenly disappeared . . . You closed down your law firm. Nobody knows where you’ve gone to.’ I said, ‘It coincides with the creation of the security service [in 1949].’ I said, ‘. . . Blind Freddy would have worked out where you were . . .’ He said, ‘Well nobody else has worked that out.’

By coincidence, too, the first director-general of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) was Geoffrey Reed, a South Australian Supreme Court justice. As a detective, Whitrod had, on many occasions, given evidence in various cases before Justice Reed.

Whitrod was hired by ASIO. He was excited. It was, he thought, work of national importance. The family moved to Sydney and Whitrod began duties in ASIO headquarters – a one-time four-storey brothel known as Agincourt. It was one of the last great harbourside mansions left standing in Wylde Street, Potts Point, after the resumption of land and construction of a nearby graving dock. Whitrod thought it was a perfect home for ASIO – built of sandstone and flanked on three sides by the naval dockyard.

The Night Dragon

The Night Dragon Jacks and Jokers

Jacks and Jokers Little Fish Are Sweet

Little Fish Are Sweet Three Crooked Kings

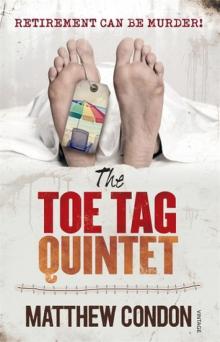

Three Crooked Kings The Toe Tag Quintet

The Toe Tag Quintet